Why at Nighttime?

Reprinted with kind permission by Dr. Brian Miller, St. Joseph Publications, Cleveland: SHE WENT IN HASTE TO THE MOUNTAIN, Eusebio Garcia de Pesquera, O.F.M., CAP.

On July 29, 1968, I arrived in the late afternoon at the waiting room of the convent of Poor Clares in Aguilar de Campoo. There, leaning against the grill, since he was a little hard of hearing and did not see very well, was an old and excellent priest speaking with two nuns on the other side of the grill. We exchanged greetings and this amusing and witty man, for some reason, unexpectedly passed a remark about the events of Garabandal: “Yes, how are those strange affairs of Garabandal that always have to take place at night as if the Virgin could not choose better hours to appear! Many things can take place in the darkness. At night all the cats are grey.â€

The good priest, lacking adequate information, had simply echoed the many rumors and prejudices circulating by word of mouth. How many times, even in the early days, had the suspicious question concerning Garabandal been asked, “Why at nighttime?†The objectors believed they had found here a good basis for distrust and rejection.

It is easy to go from questions about “nighttime†to accepting as likely the existence of other extenuating ideas like “rehearsal†and “deceitâ€â€”if not on the part of the girls, then on the part of other persons or parties putting pressure on the girls with their parents’ easily disguised agreement. I myself have heard rather weird, if not ridiculous, remarks on this matter. The surprising thing is that even Bishop Puchol arrived at such conclusions—under tremendous pressure—in a document more or less official [Nota of March 17, 1967, to the news media.].

As the girls and those close to them were repeatedly asked the question, “Why at nighttime?†they consequently passed it on to the one they saw in their trances. And this happened specifically ten days after the episode of the holy water, on September 8, a day celebrated in Garabandal since it had special Marian significance. We have a short story from that day.

With the idea of delving into the extraordinary happenings taking place there, one day I climbed the mountain leading up to Garabandal. Significantly it was September 8, the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, and I admit taking advantage of the occasion.

So Father Julio Porro Cardenoso, [This distinguished priest soon became one of the most enthusiastic and competent promoters of the Garabandal cause. He has published three books on the subject: God in the Shadows (a theological study on the events of Garabandal); The Great Prodigy of Garabandal; and Garabandal, Without Meaning?(Editorial Circulo, Zaragoza). The notes that I am using here were taken from his first book, God in the Shadows.] Canon of Tarragona, describes his first visit to the celebrated village:

We came to the place at a time when the visionaries were absent from it, since they had gone to a religious ceremony in a neighboring village that was celebrating the feast day of its patron saint.[Sometimes they celebrated the feast of the Virgin of the Sick at Puentenansa.] About five o’clock in the afternoon the girls returned to their homes, still not having eaten. Meanwhile, my good friend Father Valentin, the pastor of the place, had informed me in detail of all the most spectacular things. The rumble of thunder broke the almost sepulchral silence that surrounded us while we were exchanging impressions and I was gathering the reports that had been put down in writing and accurately verified.

Father Julio later took the occasion to examine each of the visionaries individually, asking them “as much as I could so as to clarify the events of which I had been told.†Then came the evening.

The bells of the church brought us together for the rosary. Three of the girls were present among the other children. (Jacinta was in bed with a sore throat.) I watched them and saw nothing extraordinary; they were similar to the other girls. The rosary ended and the church was closed, as the bishop had ordered. At ten o’clock at night the ecstasies began with Mari Loli in a trance.

A series of observations then followed, certainly interesting, but which we already know, since they have been repeated many times. Two things in particular attracted Father Julio’s attention: the strange movement of her clothes while the girl was falling to the ground, and her expression or deportment.

Concerning the first, he says: “Her clothes slid downwards in a movement that was not natural, as if an invisible hand were guarding the most complete modesty of the girl. All diabolical intervention has to be ruled out.â€

Concerning the second: “Loli fell slowly as though someone were lowering her to the ground; she was as if struck by a ray of light. I observed her closely; she had a truly angelic face; it didn’t seem to be the same face.â€

It was probably during this ecstasy [I later saw in the notes of Father Valentin that these questions that passed from Conchita to Loli, who had been in ecstasy in Conchita’s home, were not asked on the night of September 8, but on September 9]. that the girl, at the request of the pastor who had spoken with Father Julio about the feasibility of proposing certain questions “that would be unusual and difficult to answer,†asked the Vision among other things:

What does the Virgin most urge the Spanish people to do to amend their lives?

Answer: That they confess and receive Communion.

What sacrifice does she principally request from Spain?

Answer: That it help the other nations to be good.

What is the sin of parents that offends her the most?

Answer: That they fight among themselves: their friction and quarrels.

Certainly it was at that time that “at the request of the parish priest,†once more the pointed question was also asked: “Why do these things occur at nighttime?†[The question was asked in an ecstasy on September 8.] The answer did not come in words. The Virgin’s expression “filled with sadness.†And not only sadness: “The Virgin became grave,†Loli said later.

It is easy to understand this response. I ask myself: Could there be any other reaction from a mother toward children who show distrust, who come to her with an attitude of suspicion and doubt? Perhaps enclosed in this changed expression is a hurt reproach: For months I have come giving signs—the pure of heart understand—that it is I who am here among you, I who act, I who impart the intimate consolations of which many speak, I who give secret answers to many of your questions. And now you ask me this? Do you not have sufficient reasons to recognize me and see that, though you don’t understand them, there certainly are reasons for what I do and the way I act?

Those who find a cause for suspicion and rejection in the nighttime idea, would not react better before the proofs of the daytime, of which there are a great number. Would their attitude have been any different if they had not found the stumbling stone of the nighttime? An episode from the gospels casts some light on this: “But to what shall I compare this generation? It is like children sitting in the market places and calling to their playmates, ‘We piped to you, and you did not dance; we wailed, and you did not mourn.’ For John came neither eating nor drinking, and they say, ‘He has a demon’; the Son of man came eating and drinking, and they say, ‘Behold, a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.’ Yet wisdom is justified by her deeds†(Mt 11:16-19). “Jesus therefore said to him, ‘Unless you see signs and wonders you will not believe’†(Jn 4:48).

A person can always find reasons for not believing if there is something in believing that does not correspond to his desires. From his place in hell the rich man of the parable requested of the patriarch Abraham for Lazarus to go back in order to warn his brothers.

“They have Moses and the Prophets…â€

“No, Father Abraham, but if someone from the dead goes to them…â€

“If they do not heed Moses and the Prophets, they will not believe even if someone rises from the dead†(Lk 16:27-31).

The Virgin responded to this question with a sadness on her face, since at the base of it—on the part of some at least—there had to be a disposition neither honest nor sincere. Only she knows all the reasons for the ecstasies occurring at night. However some explanations have occurred to us. “Never,†we read in Father Ramón’s report, “have the visions and phenomena of Garabandal encouraged a big crowd; rather they have strongly encouraged the opposite. In fact, the most interesting manifestations have taken place when the mass of spectators had left.â€

Thus the fact that many of the phenomena occurred at night had a purpose of elimination. Since it was not pleasant to wait hour after hour to witness these things, after a disagreeable night, awake and almost sleepless, [In Garabandal one could not lodge in a rooming house, much less a hotel! Sometimes the village people offered or rented rooms to persons who merited special consideration, but ordinarily the people had to pass the time without sleep, or sleep as well as they could in their cars.] many abandoned the scene and left the village, especially those who had come as if on a tour to entertain themselves with a spectacle never seen before. On the other hand, those who were seriously interested remained: persons who sincerely sought something and wanted to know what this was about. And so a gathering small in number, but continuously renewed, could better observe and associate with the mystery that the girls experienced, a gathering that was physically much reduced in size.

The nighttime, the occasion so often propitious for sin, was marked in Garabandal with a sign of penance, prayer and expiation. Those who conscientiously united themselves with the heavenly walks of the visionaries, finished by experiencing the joy and the harshness of vigil hours that ordinarily left them physically exhausted and depleted. The testimonies that we can gather give an unending list of these things.[Father Julio Porro says of his first night in Garabandal: “At four o’clock in the morning of September 9,1 left the village. A vigil like this wouldn’t be worth the inconvenience, after traveling the very long trail to arrive at such an unknown mountain hideaway, if there hadn’t been something very remarkable to be present at and witness.â€]

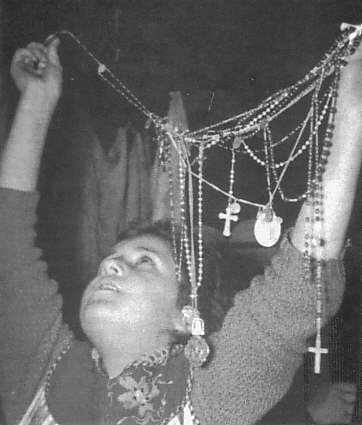

The nights at Garabandal, whatever those too wary or malicious may think of them, were not nights of sin, but rather of expiation for sin and of prayer for sinners. [What we already know about the happenings during the nights at Garabandal is confirmed by what Father Julio says about the night of September 8-9 that he experienced. Following what he says about Loli’s trance, he relates: “A series of ecstatic phenomena on the part of her and of Conchita followed…in the houses, through the streets…in the most diversified positions: standing, on their knees, completely prostrate facing the sky, seated with their arms in a cross and moving in this position through the streets, stuck in the mud and passing over the stones…. I saw them come down the stairs in Mari Loli’s home while sitting, with their arms in a cross and their gaze fixed on the heavens, without lacking in modesty in spite of their difficult posture…. They visited the sick, praying the rosary, and in that way entered into the house of Jacinta, who was in her room with a throat infection. It was exactly two o’clock in the morning; the Virgin told them to recite the rosary again…. They said it perfectly. Everything ended with the kissing of the Vision by the girls and of the girls by the Vision, and the Christian way of saying goodbye, ‘Until tomorrow, if God wills.’ The girls finally embraced, and everyone started to retire. It was past three o’clock in the morning. We had been in a constant dance from about ten o’clock. The visionaries were not tired; we were completely exhausted and drowsy.â€

It seems to me that we have here a good example of what those nights were, the nights of Garabandal that some people looked upon as suspect.]

had to be followed by whoever wanted to enter in the march, frequently perplexing, of the phenomena.[“For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few†(Mt 7:14).]

Are the “dark nights†of Garabandal something new in the experience of Christians? Do we not well know that the nighttime hours appear in the History of Salvation as hours chosen for the admirabile commercium between God and man? We can recall some well-known facts. It was at night that St. Joseph was made aware of Mary’s great secret, on which our survival depended. In the middle of the night took place the coming into the world of the Son of God and the Son of man; and the hours of the night were later those that He preferred to dedicate to prayer during His public life. But it is this same event, the Incarnation, the summit of all history and especially salvation history, that is presented to us as occurring in the mystery of the night! The Mass of Sunday in the octave of the Nativity starts solemnly with the words of the Book of Wisdom: “For while all things were in quiet silence, and the night was in the middle of her course, Your mighty word leapt down from heaven, from Your royal throne†(18:14-15). And it is evident from the lives of the saints that God gave preference to the hours of the night to communicate with them as if He were pleased to deal with His best friends during the very hours in which others usually offend Him the most.

The hours of darkness should not be so readily connected with the action of the power of darkness. It appears unfounded and unreasonable to try to find in this nighttime a sign of evil proceeding from the affairs of Garabandal. Besides anyone seeking darkness as a cloak for his wickedness does not have to search for it here; there are plenty of shadows and nights everywhere to cover the shame of an unworthy life.

Let us heed the exhortation of the apostle and “leave the work of darkness to put on the arms of light†(Rom 13:12). However, it is to be understood that this does not have any connection with the presence or absence of the sun on the horizon.

Reprinted with kind permission by Dr. Brian Miller, St. Joseph Publications, Cleveland: SHE WENT IN HASTE TO THE MOUNTAIN, Eusebio Garcia de Pesquera, O.F.M., CAP.