OUR LADY’S SCAPULAR

Reprinted with kind permission from GARABANDAL JOURNAL May-June 2005

By Father E. K. Lynch, O.C.

The Blessed Virgin appeared at Garabandal as Our Lady of Mount Carmel with a large brown scapular hanging from her right wrist. It is of great significance for her to have appeared under that title after having appeared at Fatima as Our Lady of the Rosary. The scapular and rosary are the two great Marian devotions and remind us of a saying attributed to Saint Dominic that “one day through the rosary and scapular she (Our Lady) will save the world.” But where did the brown scapular actually come from? What is its origin?

It is no exaggeration to say that the scapular devotion is as universal as the Church. It would be difficult to find a Catholic who has not at least heard of it for, as Pius XII says, it is in the “first rank” of popular devotions to the Blessed Mother. And yet how many there are who know little or nothing about the origin of the scapular.

Like many good and holy things that have come down to us from the past, the scapular (to be understood properly) has to be seen in the light of its historical setting; to take it away from the century of its origin is to deprive it of a great deal of its significance and to rob it of its value as a religious symbol.

Since the rise of monasticism, a scapular, consisting of two pieces of cloth joined at the shoulders and hanging down back and breast, has been a part of the monastic habit. The fact that it hung from the shoulders immediately suggested a spiritual meaning, for Christ spoke of the faith in terms of a burden to be carried. “My yoke,” He said, “is sweet and my burden light.” As the monk rose in the morning to begin a new day, the putting on of the scapular reminded him that he had taken the sweet burden of divine service upon him and that the day ahead was to be all for God.

When one is acquainted with the desire of the Church that we put our faith into our daily lives and sanctify even the little things of life, one can easily see how the wearing of a scapular could be a strong incentive to faithful and generous service in the vineyard of the Master. Even the sight of it could be a reminder of a promise made but easily forgotten by the ordinary person.

THE MENDICANT ORDERS

The birth and ascendancy of the mendicant orders served to strengthen the spiritual significance of the religious habit of which the scap-ular was the principal part. Coming as it did in the thirteenth century, the friar movement was bound to be affected by the feudal system which was then at its height. The friars were, by profession if not by origin, poor men who identified themselves with the poorer classes and worked in their company. Their habit, though similar to that of the monk, was actually that of the common folk. It was inevitable that the relation of vassal to lord that dominated the whole economic, social and political life of the Middle Ages would affect their religious outlook and that the timeless relation of crea-ture to Creator would be expressed in terms of it.

Living as we do in an age very different from that of the Middle Ages, we find it hard to visualize the dependence of the vassal upon his lord. While feudalism held sway, it was a matter of life and death to belong to a lord. Before the rise of towns, commerce and industry, land was the only means of livelihood; and since it belonged to the lord, one had to have the right to till it in order to live. The vassal’s act of homage gave him the right as well as that of protection, which was as important then as it is now. the right as well as that of protection, which was as important then as it is now.

Knowing how much faith and actual living were united in the Middle Ages, one can see how feudal ideas influenced religious ideas and practices and how the habit, of which the scapular is the principal part, took on a new meaning. Being a man of God, the friar was keenly aware that God is our one and only Master, but after the manner of the time, he presented himself before his Divine Master as the vassal presented himself before his lord “to pay his homage” and to receive the investiture from his hands. The religious ceremony of receiving the habit, although different in meaning, was the same as that of feudal investiture. Just as the vassal placed his hands in or between his lord’s and pronounced his oath of fealty or homage, so did the friar present himself before a superior, who took the place of God, to make his vows. The scapular, hanging from the shoulders, was an outward sign that the friar was “God’s man,” that he belonged entirely to Him and that he would pay Him the homage of his whole life. It is in this medieval setting that one must see the Brown Scapular that is the habit of the Carmelite friars in miniature form.

BROTHERS OF OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL

Before they entered the European scene, the Carmelites were a group of hermits living on Mount Carmel in Palestine. They believed themselves to be the spiritual sons of Elias the Prophet, and the life they led on Mount Carmel was patterned on his life of contemplation. The Elian tradition, however, was not the only one to influence them for long before they came to Europe, they were known for their devotion to God’s Mother. So devoted were they to her that they became known as the “Brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel,” a title they cherished and defended down through the years.

The earliest documents we have bear eloquent witness to their love for Mary for in her they found the fulfillment of the Elian ideal. She too kept all the things that God said to her, pondering them in her heart and making her life their incarnation. And it was by following her that they found the clean heart that sees God even in this life. When they made their profession, they vowed their lives to God and to her, and it was in her honor that the homage of their lives of contemplation was offered to their Lord. Mary was the Queen and Mistress of the holy mount; Carmel was her land, her vineyard, where they worked in the hope of her guidance and protection.

As a result of the Saracen invasion the Carmelites finally decided to leave Mount Carmel. It was a difficult decision to make for their ancient home had many memories for them. An old tradition holds that before their departure Our Lady appeared to them as they were singing the Salve Regina and promised to be their Star of the Sea. Fortunately they found staunch friends among the Crusaders who brought them with them on their return journey to Europe. Some settled in Cyprus, others in Italy, while others continued their journey to France and England. The English group found a benefactor in Lord de Grey, who gave them Aylesford in Kent.

SAINT SIMON STOCK

Although the Carmelites found many favorably disposed to them in the West, they also encountered much opposition, so much so that, about the middle of the thirteenth century, their days appeared numbered as an Order.

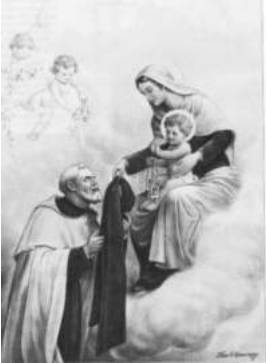

However, in 1246, at a Chapter held in Aylesford, they elected Simon Stock as their General. As he saw the waves of opposition mounting higher and higher, Simon realized that Our Lady was his only hope. The habit he wore spoke for itself for it was in her honor he had taken it. It had always reminded him that he was hers, and the long years of his life were an act of homage to her. Carmel was not his but hers; and now that it was in danger of being destroyed forever, he went to her as the vassal would go to his lord and asked her to give it her protection. Saluting her as the Flower of Carmel and the Star of the Sea, he asked her for the “privilegium,” that is, the protection a lord would give his vassals. In answer to his fervent prayer she appeared to him, and giving him the scapular of his Order she said: “This shall be a sign to you and to all Carmelites: whoever dies wearing this shall not suffer eternal fire.” The promise Mary attached to the scapular went far beyond Simon’s expectations. It saved the Order, confirmed its Marian character and made Mary more a Mother than a Queen to it.

SCAPULAR DEVOTION

One has merely to glance at the history of the Order from the thirteenth century down to the present to see how the scapular vision served to strengthen its devotion to Mary. And the external sign of that love and devotion through the years has been the Brown Scapular.

The words of Our Lord: “My yoke is sweet and my burden light” was the inspiration for the scapular worn by monks from the beginning of monasticism, and continued today (such as these Trappists). It was to the scapular of the Carmelites that Our Lady gave her great promise and which was extended to the whole Church in the small brown scapular worn by the faithful today.

Some people are inclined to exaggerate the importance of visions and private revelations, and in assessing the spiritual value of the scapular devotion one must keep in mind the teaching of the Church regarding them. It is the constant teaching and practice of the Church that devotions must be founded on revealed truth and that visions and private revelations have relative value only: they serve to focus attention on some truth God has revealed and must be interpreted in the light of it. The popular devotion to the Sacred Heart is not based on the revelations to St. Margaret Mary but on the Incarnation of the Word. The same must be said about the Lourdes and Fatima devotions. The visions of Our Lady called attention to her role in the economy of redemption and to the old Christian doctrine of prayer and penance.

It is in this context that one must see the scapular devotion. It is based on the spiritual motherhood of Mary in the setting of Carmelite history. The total dedication of the Order to her made the scapular a sign of consecration to her. And what more fitting sign could one find of her spiritual motherhood than a garment. When she brought forth her Firstborn she wrapped Him up in swaddling clothes and it was she who wove the seamless garment by which He was known. The Carmelite habit has always drawn minds and hearts to her and been a sign of her loving protection.

For a long time the habit was the exclusive property of the Order, a sign of profession in it and of the life totally consecrated to her, but in the fourteenth century we find a bridge appearing between Carmel and the world. Pious people living in the world became anxious to live its Mari-form life and to share in its spiritual treasury of prayer and good works; and as a visible sign of their affiliation to the Order they were given the scapular. This was the beginning of the third order of Carmel and of the confraternity. These good people were often generous benefactors and in return for their help the Order granted them a share in all its Masses, prayers and good works. With the lapse of time this participation was given without any financial assistance.

Here we find the two essential elements of the scapular devotion. Consecration to Mary in Carmel and participation in the spiritual life of the Order.

In a comparatively short time the wearing of the scapular spread to the whole Church and became the unmistakable mark of the good Catholic. Popes, kings, princes, nobles and humble folk alike lived and died in the hope of the promise made to St. Simon, and the scapular devotion grew to be one of the leading devotions to the Mother of God. As a Marian devotion it has stood the test of time, and the seven centuries that have elapsed since the vision have served to reveal its beauty. It has kept generation after generation aware of its duty to call Mary blessed, and in the homage paid to her, countless saints have come to realize that to find her is to find life in her Son and to draw salvation from Him.

Reprinted with kind permission from GARABANDAL JOURNAL • MAY-JUNE 2005

to order subscription: GARABANDAL JOURNAL.

Back for more Garabandal Information